70. Dr. Ben Carson, a brilliant pediatric neurosurgeon, is now the Secretary of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), because he’s….Well, I suspect the internal discussion went something like this: The U in HUD stands for “urban,” and, as Paul Ryan showed us, “urban” is a code word for “black.” So, let’s make Ben the head of HUD. A match made in Heaven or wherever, quod erat demonstrandum.

(By the way, this post will be about food. I promise.)

Anyway, back on March 6, 2017, his first day in office, Dr. Carson spoke to his HUD employees, declaring: “That’s what America is about, a land of dreams and opportunity. There were other immigrants who came here in the bottom of slave ships, worked even longer, even harder for less. But they too had a dream that one day their sons, daughters, grandsons, granddaughters, great grandsons, great granddaughters might pursue prosperity and happiness in this land.”

Let’s just say that the world of social media noticed. The Food Network’s Sunny Anderson had one of the more restrained reactions:

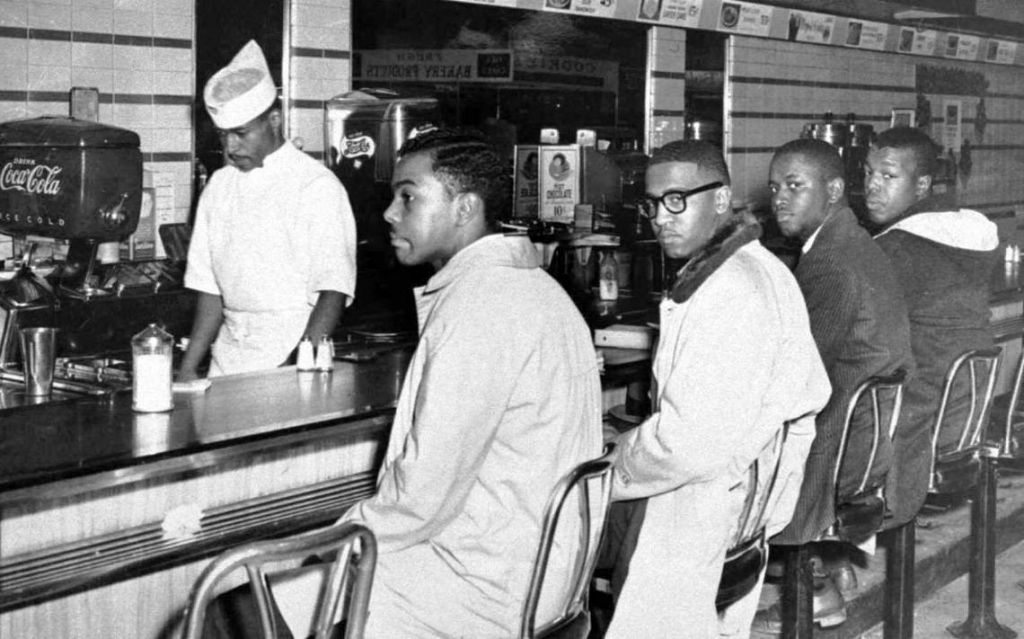

Carson’s statement did seem odd. When we think of “immigrants” coming to America, we probably don’t picture it like this:

Carson’s statement did seem odd. When we think of “immigrants” coming to America, we probably don’t picture it like this:

Later in the day, on his first attempt to talk his way out of it, Dr. Carson appealed to a linguistic technicality: An immigrant might be defined as an individual member of a migration. Some migrations are voluntary, and some are not. (Ask the Cherokee people about the “not” version.) And so, it was as he first said: The enslaved were “involuntary” immigrants.

Well, ok. Some still objected. Jelani Cobb noted that calling an enslaved person an “immigrant” is like calling a kidnapping victim a “house guest.” At the time, slaveholders insisted that they were merely importing farm equipment, like a farmer today might import a Volvo tractor. The enslaved were considered property, not tourists. (Except when it came to seats in Congress. Then the slaveholders wanted their “property” to count the same as them. That’s where the infamous 3/5ths rule came in as a compromise.)

But even if we’re charitable and grant Dr. Ben that technical definition, it still wouldn’t explain his characterization that the enslaved had “worked even longer, even harder for less” in order to win the American Dream for their descendants.

On the face of it, it sounds like a backhanded argument against raising the minimum wage. Can’t make it on $7.25/hr? Stop whining, and work 16 hours instead of 8.

If that’s your politics, fine. But don’t compare it to life under enslavement. If we say they were working “for less” instead of “for free,” then we’re assuming that the enslaved at least got “paid” in free room and board, so it was ok. I mean, a hovel and a cup of cornmeal is worth something, right? There’s no free lunch.

And the rest of your “compensation”? Whippings were thrown in for free. Character-builders, I guess. Maybe Frederick Douglass wouldn’t have gotten up the gumption to escape and become an abolitionist hero if he hadn’t been beaten up so much.

Fact fact (not an “alternative fact”): Many of the enslaved who escaped made their way to Canada. What do we make of that? Carson said the African immigrants dreamed that their descendants “might pursue prosperity and happiness in this land.” But for many, “this land” was Canada, not America. So were they just un-American ingrates who didn’t realize how good they had it here? (See painting above….)

And while we’re at it, the enslaved weren’t quite allowed to have dreams for their descendants, because those descendants automatically inherited their enslaved status, simply by being born. They were, legally, the property of another person from birth. The tragic reality was something more like this newspaper clipping found by Michelle Munyikwa:

Before the day was over, the good Doctor was in full retreat. Carson insisted that he knows the difference between slavery and immigration. But that’s not so obvious. As Tera Hunter pointed out, this wasn’t the first time that Carson has waded into this swamp. He has compared Obamacare to slavery. He has compared reproductive freedom to slavery.

2014: One of the good ones had the guts to speak up

That rhetoric plays well on the right. Some insist on minimizing the horribleness of American enslavement, like Bill O’Reilly’s ridiculous comments last summer about “well-fed slaves.” We just don’t expect to hear it from a guy with ancestors who were, we assume, enslaved.

Bill O’Reilly, between lawsuits, pronounced slavery not so bad

But let’s turn the clock ahead to the early 20th century. Now, talk of “immigrants” (or more accurately, “migrants”) dreaming of a better life might be more plausible. We’re referring to the period known as “The Great Migration,” lasting from World War I into the 1960s, when millions of African Americans managed to leave the southern states for the north and west.

In this case, we certainly have the element of free choice. Indeed, as Carol Anderson summarizes in the second chapter of her book, White Rage, the southern white power structure used every tool at its disposal, short of starting another Civil War, to prevent African Americans from leaving. By that measure, it was the opposite of a forced migration.

We also have the motives that traditionally lured Europeans to America. Some went northward in search of better economic opportunities than were available in the segregated economy of the south. Others were running for their lives, seeking to dodge the renewed outbreak of lynchings and violence encouraged during the Woodrow Wilson administration.

In this sense, one might compare the experience of African American migrants in the north to the experience of foreign immigrant groups across our history, from the Germans, Irish, Scandinavians, Chinese, Italians, Mexicans, Koreans, and Vietnamese, to the Somalians, Ethiopians, and other more recent arrivals.

Food. Talk about Food…

For many reasons, migrants often seek out the food they ate back home. Opening small operations, such as cafes, food stands, pushcarts, and catering businesses has been a first step available for many minority groups in the face of racism, bigotry, and restriction.

Then, two things happen. First, the original “ethnic” dishes begin to take on the flavor of their surroundings. That was certainly the case for African American migrants. Some of the ingredients that were common and cheap down south were either unavailable in the north or their seasonality was more restricted. Much of today’s debate over yellow cornbread vs. white cornbread, for example, stems from the simple reality that up north, yellow cornmeal is what’s more likely to be on the grocery shelves. Northern wheat flour is different too.

We see this in the various menus of the Sweet Home Cafe at the Smithsonian’s new National Museum of African American History and Culture. What we probably think of as “soul food” is well-represented by the “Agricultural South” menu, with items like fried chicken, collard greens, mac and cheese, Hoppin’ John, and so on. The “Creole Coast” menu, representing the Low Country and Louisiana traditions, still sounds like soul food, with items like fried catfish (as a Po’Boy sandwich), and candied yams.

But as we move into the “North States” and “Western Range” menus, we run into items that don’t sound like “soul food” at all, like smoked Haddock, Yankee Baked Beans, “Son of a gun” Stew (with beef short ribs), and BBQ Buffalo brisket.

Sweet Home Cafe: soul food surrounded by history (NMAAHC photo)

These menus remind us that “soul food” is more than a particular list of dishes or ingredients. As a general rule, “soul food” dishes are characterized by close attention to seasoning, no matter what the dish is. There’s also that more esoteric quality of putting “love” or “soul” into the cooking. That’s impossible to pin down scientifically, but we know whether it’s there or not.

Both distinctions are important. Sometimes, we make “soul food” shorthand for “what black people eat.” By that measure, a Big Mac is soul food. In some areas, food redlining, like housing redlining, has helped create or reinforce segregated neighborhoods where people without sufficient money, transportation, or free time often end up going to the ubiquitous fast food places to grab cheap items made from government-subsidized ingredients. A Big Mac may not be a nutritionist’s dream food, but it is an economical way to get a lot of calories in a hurry.

No offense to the good folks at McDonald’s, but Big Macs are the antithesis of “soul food.” They’re not particularly well-seasoned, and it’s hard to put that indefinable element of “love” into food designed to be mass-produced quickly with minimal human intervention. There’s also no sense of down-home regionality in a Big Mac. Franchising’s raison d’être is that sandwich you buy in Bangor, Maine should taste like the one you buy in Pensacola, Chicago, Topeka, Sioux Falls, Salt Lake City, Oakland, or whatever McDonald’s in DC is closest to the NMAAHC.

Just don’t call it soul food

On the positive side, the historic regional flexibility and adaptability of African American cuisine offers a key to its survival. Fair or not (and in this blog, we say Not), many criticize the traditional soul food menu as unhealthy. But there’s no reason why soul food restaurants can’t include lower fat, less sweet items or vegetarian/vegan items and still be made with love and good flavor. The African roots of soul food point to an emphasis on vegetables over meat, and developing flavors beyond what we can get from fats and sugar. “Soul food” was inherently adaptive, and still can be.

The other thing that happens to migrant foods is more challenging: As migrant groups become more fixed in the community, people from outside that group start frequenting the local eateries, and over time, the food itself changes to meet the tastes of the new customer base. Americanized versions of Chinese, Italian, or Mexican dishes are typically unrecognizable to visitors from those nations. The taco you buy at a Taco Bell in Minneapolis is not like the taco you might buy from a food truck in Los Angeles, let alone one from Mexico.

Midwesterners have discovered this with the influx of Latin American immigrants in the last twenty years. Here in Sioux City, when we’re sorting out dinner plans, “Let’s have Mexican!’ is inevitably followed by “You mean real Mexican or Taco Bell?” Many local Mexican restaurants cater to both tastes. For instance, you can usually order a taco “American style” (i.e., with cheese, ground beef, and no cilantro).

One meme put the issue succinctly. Don’t look up chingadera. Use your imagination.

Even the “real Mexican” menu is an invention. There is plenty of regional diversity in Mexican cuisine, and most restaurants pick and choose. Some “real Mexican” restaurants around here include Dominican or Guatemalan dishes, in an attempt to cater to the needs of as many groups as possible.

How far can “authentic” soul food be stretched before it becomes something else? I’ve heard it said that “southern” cooking is nothing more than soul food dumbed down in taste, fancied up in looks, and boosted up in price. I can order fried catfish and a side of collards at the Cracker Barrel, and it’s ok…but it’s not quite soul food either.

In real estate, “gentrification” describes the phenomenon of young white professionals moving into older, predominantly African American neighborhoods in search of cheaper rents or home prices. They fix up their houses, and open up coffee shops and such. In the process, property values increase, rents go up. Then, those without the incomes to support the new requirements find themselves being driven out.

In 2015, “Saturday Night Live” doctored up a real-life business in Bushwick to create their “Martha’s Mayonnaise” spoof of what happens under gentrification in Brooklyn.

Recently, this phenomenon of “gentrification” has been applied to soul food.

Two things happen with gentrification: First, we risk losing the historical significance of soul food. Think of it this way: There’s nothing more All-American than hamburgers and hot dogs, but we never think of their German roots. What was the “Hamburg” style of meat? Do we ever stop to think that “wiener” refers to Vienna? Does eating a chicken and roadkill hot dog oozing with white filler move us to seek out the rich sausages of the Central European tradition? Likewise, if soul food survives by the gentrification route, would it get disconnected from its soul?

Gentrified German soul food

Second, with gentrification, the people who created soul food may well be left out in the cold. On the eater’s side, Eboni Harris noted the phenomenon of how “‘ethnic’ foods are ‘discovered’ by well-meaning foodies – often white – who then raise the price of these meals until the original purveyors and consumers can no longer afford to eat them.”

Once upon a time, for instance, oxtails were considered so useless that some butchers gave them away for the asking. Today, oxtails are expensive, especially considering the small amount of meat on them. Barbecue aficionados have noted the same when it comes to brisket.

This is significant for soul food because one of the historic keys to soul food was in the ability of African American cooks to apply the legacy of West African cuisine to make less desirable foods, like neckbones or collards, taste great. But it’s hard for the average person to practice cooking and perfecting traditional dishes if the ingredients break the budget. (When I wanted to make oxtails, I practiced on cheaper stew meat before I dared invest in actual oxtails.)

On the cook’s side, we run into appropriation, aggravated by the multitude of ways in which institutionalized racism hinders African Americans from being able to capitalize on their food heritage. The difficulties faced by trained African American cooks in becoming chefs are quantifiable. We can work our way through the lists of the annual James Beard award winners. We can count up the black chefs that make it onto Chopped episodes, or check cookbook sales.

Last fall, there was a minor media fluff over Neiman-Marcus selling collard greens. We titled our reaction, “Greens for People Better Than You.” The gist of the piece was to wonder why anyone would pay so much for frozen greens rather than go to a local soul food restaurant and by some fresh greens for a fraction of the cost, and probably with superior flavor to boot.

Robert Irvine no doubt makes fine collard greens. Does it matter if his face becomes the face of collards, and his seasoning sets the standard?

For some, this is when “gentrification” begins to sound more like flat-out appropriation: white folks coming in and taking over, obscuring the history, and making money off of other people’s food traditions and hard work, while using the tools of contemporary segregation, such as equal access to capital, to shut out or shut down competitors.

It’s a double injustice. Many southern/soul food dishes were created or perfected by enslaved cooks paid nothing, or by underpaid cooks working under Jim Crow. Spin the clock ahead to 2017, and their descendants are feeling cheated again. Many soul food places are closing down just at a time when southern cuisine and barbecue are coming to national attention and popularity.

At that point, the broader quest for social and economic justice will have an impact on the fate of soul food. If the arc of the moral universe really does bend toward justice, the impact will be positive. The restaurant business is always challenging, but people who want to cook soul food, or include soul food dishes, will benefit from increased opportunities to follow their dreams.

Those of us who like to eat and/or cook soul food have a moral obligation to those who passed it down to us to invest ourselves not just in groceries but in the broader quest for justice. That requires, in the first place, knowledge. We should learn the history behind the cuisine, and also understand the current situation. More on that in a moment.

Soul food may also benefit from a renewed interest in home cooking. Some watch food programming on TV just for its entertainment value, but others get curious enough to try their own hand at things. I can tell from the new options on the grocery shelves at my neighborhood Walmart that people’s kitchen horizons must be broadening.

For some, cooking is a lost art. I’ve had the disconcerting experience of being asked to give advice, tips, or soul food recipes to younger African American women. I’m always flattered, but it just feels weird that they’re asking an old white guy for something that would be better learned from their parents or grandparents. What do I know? I’m just a student myself, and a pretty elementary one at that. I feel like John the Baptist meeting Jesus: “You want me to baptize you? Dude, you should be baptizing me!”

Cooking takes time and practice, a willingness to learn by trial-and-error, screw up a dish, apologize to your family…and then come back and try it again. The current level of interest in cuisines and cooking may give soul food a boost, both in terms of learning to cook them the old-fashioned way, and in adapting the classics to meet our interest in healthier options.

Hopefully, this hands-on practice in the kitchen may also get more people interested in the history behind the soul food. It’s in the nature of that cuisine that some of us are curious about what has gone into the “soul” part.

We know how this works in music. When Chuck Berry died in March, many of us on the downhill half of life’s mountain climb paused to reflect on the music of our childhood.

Chuck Berry in London, 1965. His music ended up teaching me more than music.

Like a lot of white teenagers in the 70s, I discovered Chuck Berry retroactively. I had learned his songs first from the covers done by the Beatles and the Stones. But then I got interested in going back and finding Berry’s originals, and that, in turn, led me to dig back even further into the roots of rock and roll in the r&b and jazz of the 1930s and ’40s. It wasn’t just the music either. Learning how the Delta blues became the Chicago blues, for instance, led to my introduction to the topic of the moment: the Great Migration.

The same has been true in exploring soul food. It prompted me to go back and learn a lot of history that I was never taught in school, and then to think about how that history continues to impact us. This blog reflects some of that journey. I’m sure some react to putting food and history together the same way that some react to putting pineapples on pizza. But I like it.

So, the question of authenticity may solve itself. Some will surely try to capitalize on dumbing-down soul food dishes for a broader audience, but others will respond by offering something more faithful to the living traditions.

Bottom line? Food is always in transition. Techniques, equipment, ingredients, and tastes change. “Soul food” isn’t a museum piece. It’s a living cuisine, and it would be inauthentic to try and somehow freeze it in time. Even the name may change. “Soul food,” after all, was a 1960s invention. The great Edna Lewis, it will be remembered, called it “country cooking.” But my educated guess is that it, whatever “it” is, will survive.

Carson’s statement did seem odd. When we think of “immigrants” coming to America, we probably don’t picture it like this:

Carson’s statement did seem odd. When we think of “immigrants” coming to America, we probably don’t picture it like this: